Canadian Nationalism Is Back. Now What?

A long read on the complex history of Canadian nationalism, the Canada-US relationship, trade and tariff policy as identity, and the urgent need for egalitarian nation-building in the age of Trump.

If you’ve been following my work here, it won’t surprise you to learn I’ve been thinking a lot on the question of nationalism these past few months. The subject has always been of general interest to me, but I’ve long found its history in the country of my birth particularly compelling. Even if you’re a non-Canadian reader (which Substack’s analytics tell me you’re statistically quite likely to be), it also shouldn’t surprise you to hear that recent events in the United States are continuing to have profound political and cultural implications where I live — or that the question of Canada’s identity has been thrown into sharp relief thanks to the behaviour of Donald Trump.

With all this in mind, I’m eager to share my latest essay, written for The Walrus magazine. In it, I do my best to explicate the complicated history of Canadian nationalism and the extent to which one of its key fulcrums has been the question of trade with the United States.

What’s so interesting is that this has remained the case from Canada’s inception as a union of disparate British colonies right through to the present day. Nationalism in Canada has thus had many different expressions over the past 158 years, something made especially visible during the multiple federal elections fought either exclusively or near-exclusively over the question of free trade: 1891, 1911, and 1988 (to this list, we might as well add the still ongoing 2025 election as well, given the centrality of trade and tariffs to the campaign). From its conservative and colonial roots, Canadian nationalism gradually transformed into something with a strongly social democratic and egalitarian ethos.

As I write in the piece:

Since 1867, Canadian nationalism has been as motley and diverse as the country itself. But among nationalists of every kind, the presence of the American leviathan has invariably loomed larger than anything else. This is why, from Canada’s very inception as a nation-state, the trade issue has never been strictly reducible to the intricacies of economic legislation or the management of border policy. Without exception, it has also been enmeshed in deeper, more existential questions of culture and identity, inseparable from wider debates about Canada’s self-conception as a political community.

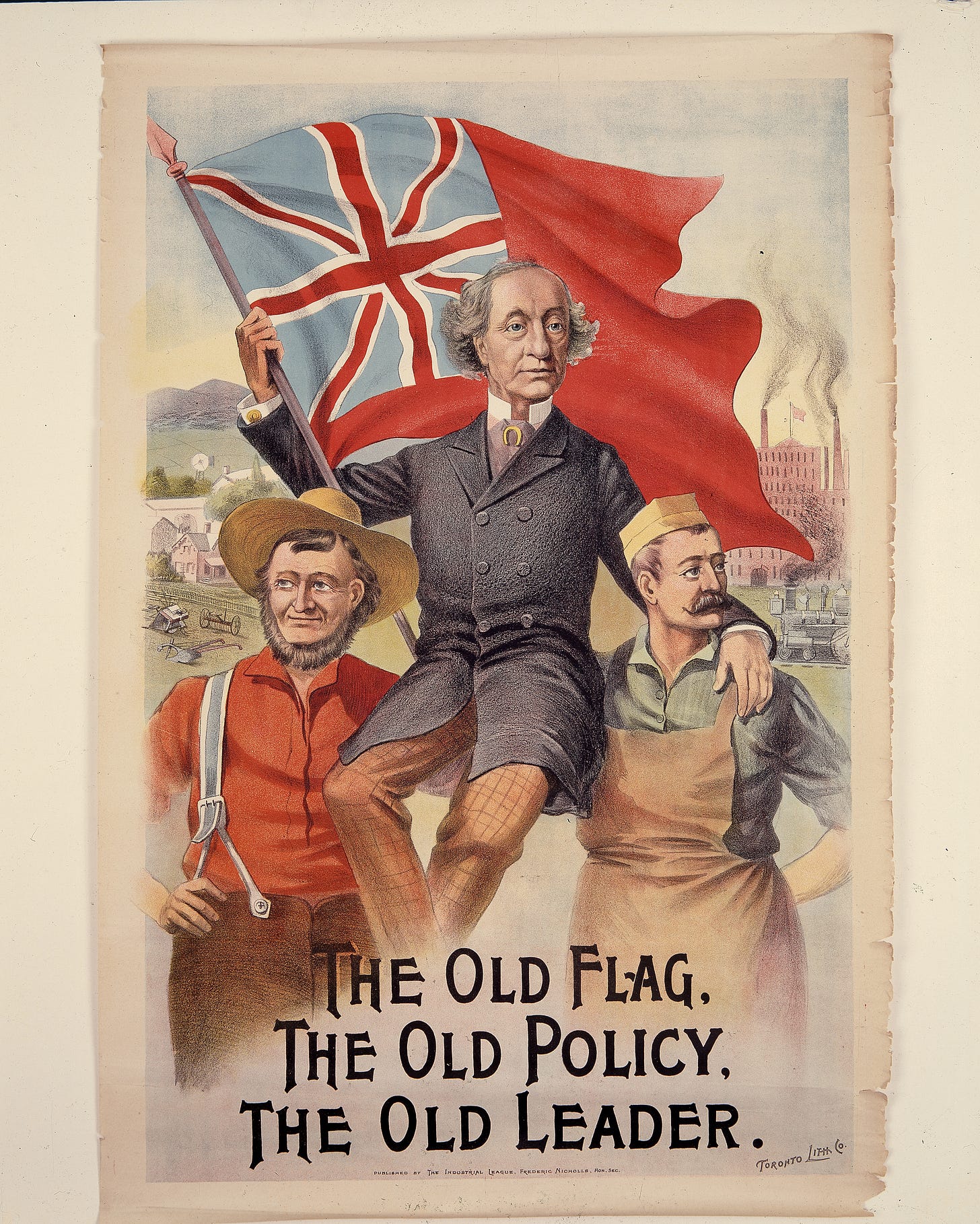

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this was mainly because the dominant culture was conservative, colonial, and British. When he staked the 1891 federal election on the preservation of tariffs, John A. Macdonald pledged to show “the Americans that we prize our country as much as they do and that we [will] fight for our existence,” adding, “A British subject I was born, and a British subject I will die!” Meanwhile, in championing a policy of free trade, the Liberal Wilfrid Laurier, born in what is now Quebec, would go down in defeat. Under the successive Liberal administrations of William Lyon Mackenzie King, trade was eventually somewhat liberalized. In the postwar years, however—as Canada grew more independent, democratic, and multicultural—the most vocal critics of integration with the US increasingly became progressive liberals and members of the social democratic left.

It’s obviously with this latter tradition that I most strongly identify.1 And, in light of Canada’s ongoing debate over how to respond to Donald Trump and everything that encompasses — identity, trade policy, the economy, social inequality — my essay makes the case for a revival of its best elements. When I first conceived it, I was probably a bit more optimistic about this happening in the immediate term than I am six weeks later. Right now, the version of Canadian nationalism that seems ascendent is mostly of the technocratic and small-c conservative variety. For reasons I’ve detailed elsewhere, I don’t find this at all attractive. But I don’t find it particularly coherent either.

To quote from the essay again:

In response to Trump’s unprovoked policy of economic warfare, Canada’s politicians have at least temporarily re-embraced protectionism and ventured into ideas like new pipelines and deregulated interprovincial trade. Against the current political backdrop, however, policies such as these can sound a whole lot more novel and groundbreaking than they really are—reflecting a vision of nation building firmly within the prevailing orthodoxies of neoliberal Canada.

With a patina of nationalist rhetoric attached, it seems, virtually anything can be made to sound patriotic. In the hands of social democrats and progressive liberals who popularized it during Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, “masters in our own home”—a phrase Mark Carney has taken up—once implied the nationalization of energy, the expansion of the welfare state, and a zealous commitment to activist government. Today, it can just as easily mean cutting the capital gains tax and subsidizing the fossil fuel industry.

In any case, I’ll let the rest of the piece speak for itself. Enjoy.

One limitation of the piece is the relative absence of Quebec from the story it tells. The history of nationalism in Quebec is something that interests me a great deal as well, but it’s also a story too long to incorporate into a piece like this.

I wonder if you have read Land of Cain by Phil Resnick, a class analysis of English Canadian nationalism.