Socialism is an optimistic creed, based on a fundamental assumption of the equal worth of all men and women, and the greatness of the human society that they can create through their collective endeavours. It is a philosophy of compassion, believing that each is responsible for the welfare of all. It is a doctrine of courage, prepared to challenge those who would maintain privileged positions through the exploitation and oppression of others. - Ed Broadbent, 1975

First off, I apologize that it’s been 10 days or so since my last post. I’ve spent the last week in Ottawa as part of ongoing work with Ed Broadbent’s papers at Library and Archives Canada, and to speak about Ed’s thought at the Broadbent Institute’s annual Progress Summit. What follows is the text of my remarks at the Summit on Thursday, which focused on how Ed approached the question of nationalism from the left and what we can learn from his example in a moment of heightened US belligerence and resurgent Canadian nationalism.

If you’re a non-Canadian reader, you might be surprised to learn that, throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, the socialist left was the default home for many of Canada’s most prominent and influential nationalists. One reason for this is that much of Canada’s resource sector, along with key parts of its economy, boasted high levels of American investment and ownership. This high level of foreign control meant not only the loss of quality manufacturing jobs in Canada, but also the significant loss of democratic sovereignty.

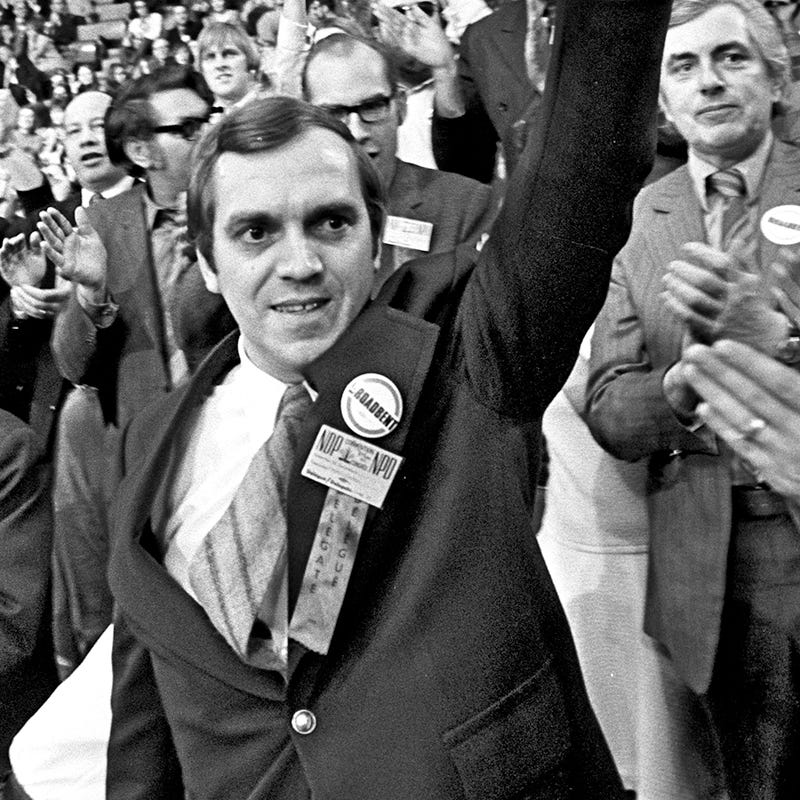

Before my late friend Ed Broadbent entered Parliament in 1968, he was a professor of political science at York University — and it was during this part of his career that the episode I describe in my remarks below took place. The following year, Ed was elected to represent his hometown of Oshawa, where he remained an MP until 1990. In 1975 he was elected leader of the NDP (Canada’s social democratic party) and remained vocal about the threat of US economic domination throughout his tenure. A few weeks before his death in January 2024, we published our book Seeking Social Democracy — which contains a dedicated chapter on Ed’s relationship to nationalism these issues in greater detail. Enjoy.

Good afternoon.

Our remit for this panel was fairly wide and, in light of that, I was tempted to try and speak in a general and open-ended way about our late friend Ed Broadbent — about, perhaps, his thinking on the issue of inequality or his conception of democracy. But in light of the particular moment we now find ourselves in as a country, I’m instead going to focus on his thinking in one very specific area that’s of singular importance right now — namely, the question of nationalism.

I want to tell you about a particular episode from Ed's career that I think is very relevant in the present moment and gives us a lot to think about at a time when (for reasons I don’t think I need to specify) nationalism is very much a live political question in this country again. I also chose this story because, even though it’s related to nationalism, I think it has plenty to say about Ed’s wider political vision as well. And, for that reason, I think it should give us plenty to talk about in the discussion to follow.

So, to begin.

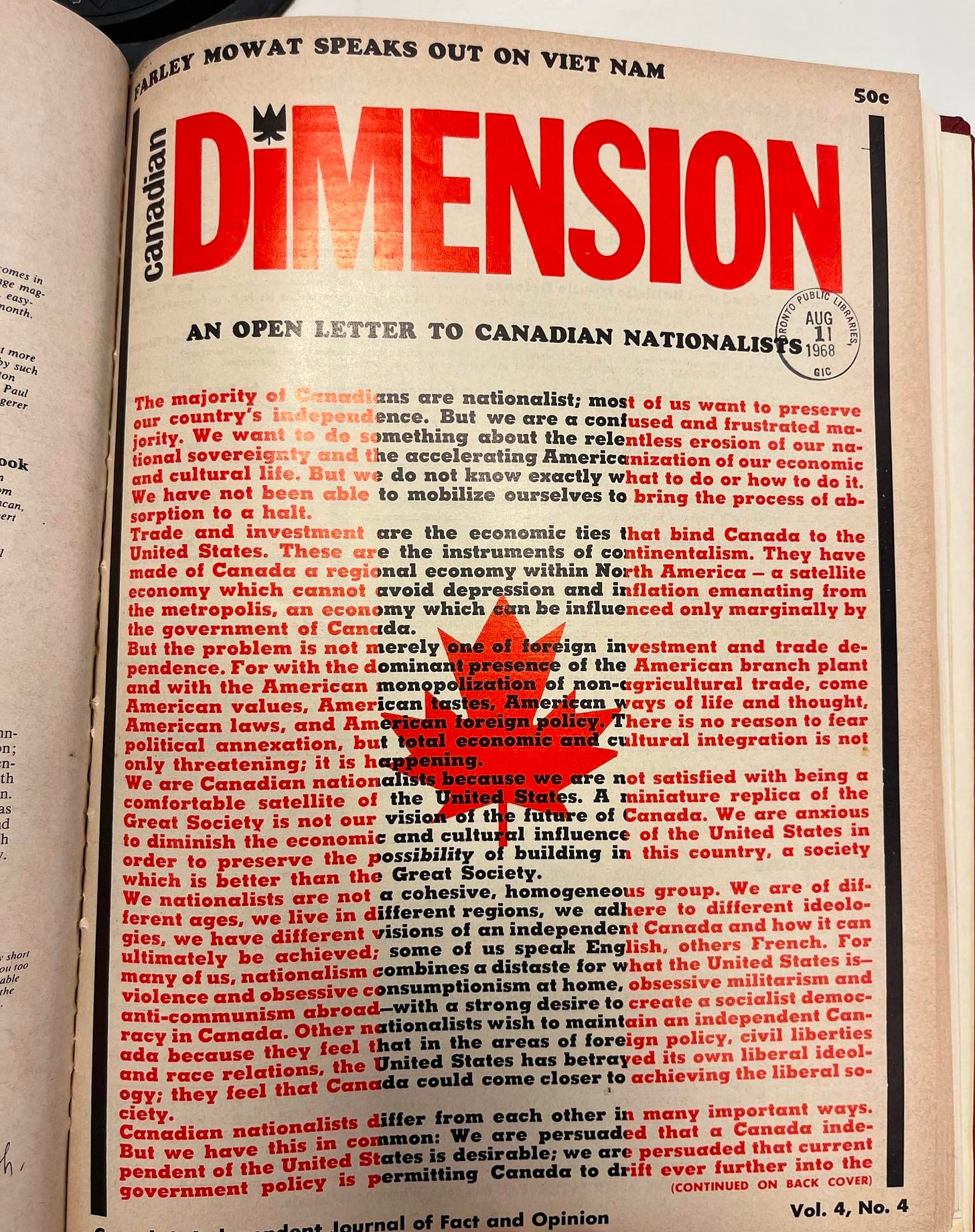

In 1967, the editors of Canadian Dimension — one of the intellectual homes of left nationalism — published an urgent call for political cooperation across the left-liberal divide. Entitled “An Open Letter to Canadian Nationalists”, the letter made the case for a broad alliance bringing together socialists and liberals who were concerned about the growing Americanization of Canada and the threats posed to its economic sovereignty by US corporations operating north of the border.

They wrote:

“We want to do something about the relentless erosion of our national sovereignty and the accelerating Americanization of our economic and cultural life. But we do not know exactly what to do or how to do it. We have not been able to mobilize ourselves to bring the process of absorption to a halt. Trade and investment are the economic ties that bind Canada to the United states. These are the instruments of continentalism. They’ve made of Canada a regional economy within North America – a satellite economy which cannot avoid depression and inflation emanating from the metropolis, an economy which can be influenced only marginally by the government of Canada.”

At this moment in Canada’s history — more than 20 years before the advent of free trade — the question of our survival as a nation state, of our long-term viability as a country, was not only a live issue, but something that cut across almost of the traditional regional and partisan divides. All three of the major parties — not just the NDP — had nationalist wings. In 1965, the bestselling nonfiction book in the country was George Grant’s Lament for a Nation (a book that, in declaring the death of Canadian nationalism, ironically played a quite significant role in inspiring and reinvigorating it.) So, in this context, I suspect what the editors of Canadian Dimension were saying about the need for a broad nationalist coalition made up of liberals and socialists strongly resonated with plenty of readers and probably sounded like common sense.

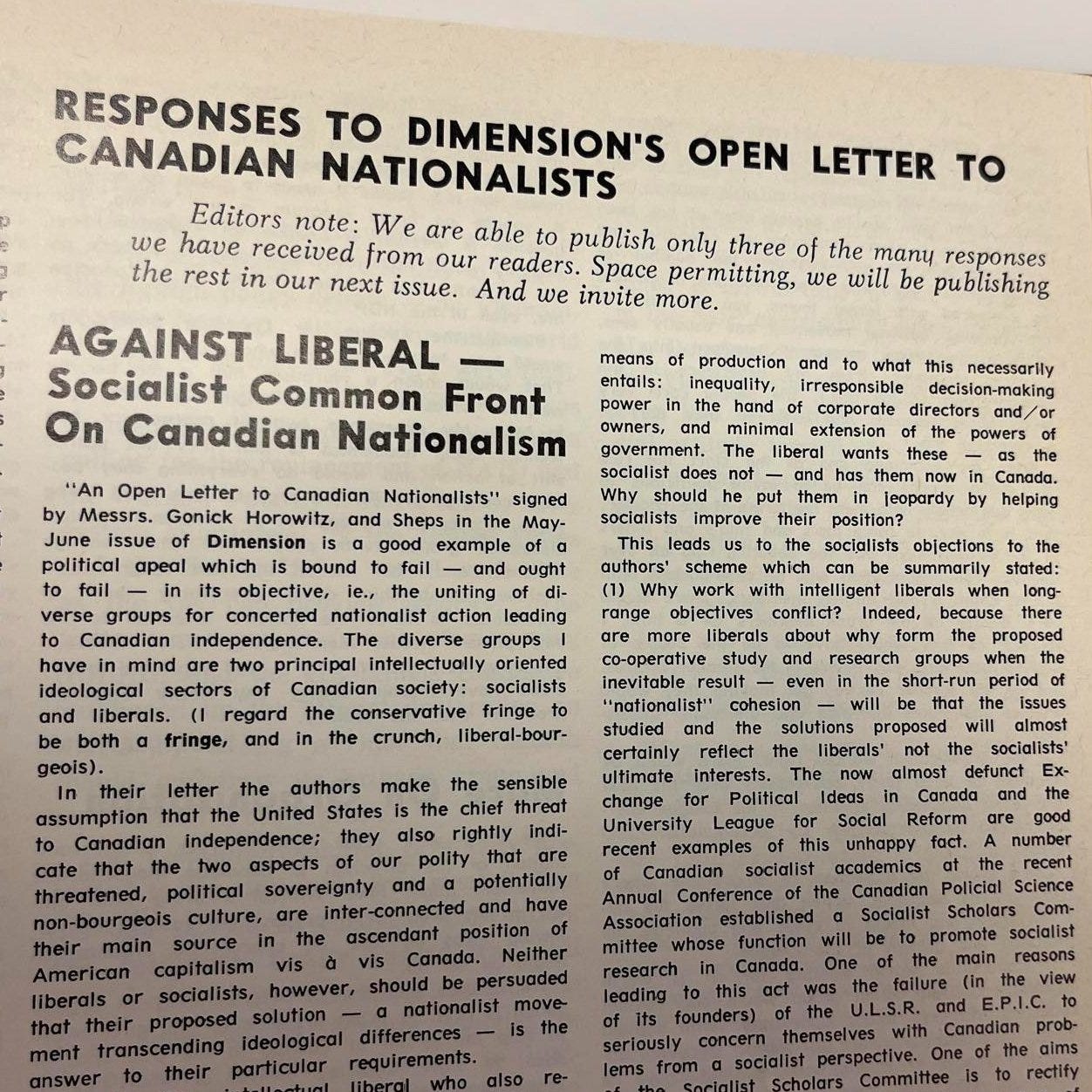

One precocious young political science professor at York University, however, strongly disagreed. Writing in the subsequent issue of Dimension, Ed Broadbent argued forcefully against the idea of cooperation between liberals and socialists on nationalist grounds.

I should pause here to note that we recently published both letters on the Perspectives Journal website so you can read them for yourselves there. But the crux of Ed’s argument was this: as he put it to Dimension’s readers, liberalism and socialism or social democracy — Ed always used these terms interchangeably — were distinct philosophies that were committed to such radically different ends that the idea of cooperation was not so much impossible or even inadvisable but incoherent:

“The consistent liberal is committed to private ownership of the means of production and to what this necessarily entails: inequality, irresponsible decision-making power in the hands of corporate directors and/or owners, and minimal government. The liberal wants these — as the socialist does not — and has them now in Canada. Why should he put them in jeopardy by helping socialists improve their position?”

So this was the main thrust of Ed’s argument against the idea of building a liberal/socialist coalition around the national question — and it speaks to something that was absolutely consistent from the 1960s through to the end of his life. Ed was eager to work with liberals and with non-socialists (be they Red Tories or Soviet dissidents or Sandinista revolutionaries) whenever he saw an opportunity to advance the pursuit of human rights, to fight poverty and discrimination, to make gains for workers — whether autoworkers in Oshawa or garment workers in Thailand, and so on.

But, whether it came to the national question — and, indeed, most other big political questions — Ed fundamentally saw social democracy as something distinct (not only from conservatism, obviously) but also from liberalism or “progressivism” as it’s sometimes called today. The difference between social democracy and liberalism, and the corresponding difference between a party like the Liberals and a party like the NDP was ultimately a difference of kind rather than of degree. Socialists, for Ed Broadbent, were not simply liberals in a hurry.

For him, the pursuit of democratic socialism was the organizing principle around which everything else revolved. And this applied especially to his nationalism. To Ed, the cause of preserving Canada’s economic and cultural sovereignty was necessarily connected to the wider issues of class inequality, corporate power, and worker’s rights that left parties were created to address. He put this quite bluntly and powerfully in his response to the editors of Dimension, writing:

“Socialism not nationalism or liberalism is the sole justification for wrenching Canada free from American domination.”

I chose this anecdote not just because I happen to particularly enjoy it, but also because I think Ed’s 1967 letter to Canadian Dimension offers us something very important and useful in a moment like our own. There was no point to nationalism — and no real point in being a nationalist for Ed — unless that nationalism was linked to the wider project of building democratic equality.

In the 1980s, when campaigning against Brian Mulroney (a free trader) and John Turner (a liberal nationalist), he compared them, respectively, to Wall Street and Bay Street. This was, I think, more than just a good piece of campaign rhetoric. For Ed, I think it also reflected a deeper belief that an unequal and unjust society is still an unjust and unequal society whether we happen to be hearing rousing patriotic slogans from our CEOs and leaders or not. That was true in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and it remains every bit as true today.

Thank you.