Politics in the passive voice

All the world's a stage and the meta-narrative has become our God. Long live the new flesh.

In one scene from the 1993 documentary film The War Room, Bill Clinton advisor George Stephanopoulos races from a suite where he and his fellow operatives have been viewing one of Clinton’s debates with George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot to an adjacent venue where the media has assembled to hear post debate spin. Beforehand, Stephanopoulos dispenses instructions to those around him: “Keep repeating Bush was on the defensive! Bush was on the defensive all night!” Moments later, he offers a version of the same line to reporters: “Another great night for Bill Clinton. Three debates, three wins. Bush was on the defensive all night long.”

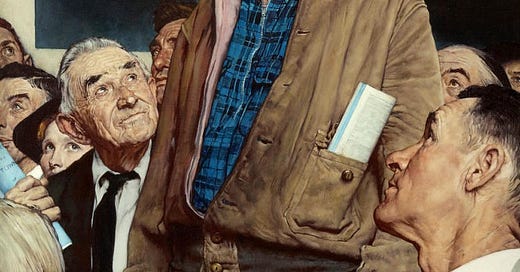

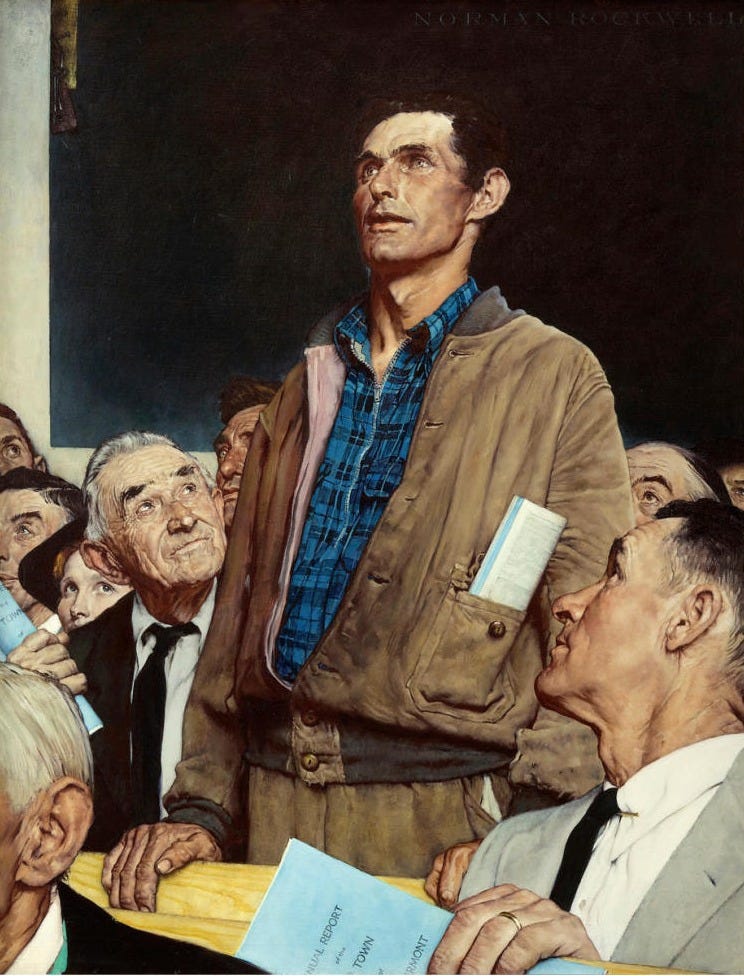

As a behind-the-curtains look at the Machiavellian world of the campaign backroom, the film gazes on all of this with wide-eyed wonder. While Stephanopoulos and James Carville pour over numbers quantifying viewer reactions and tailor their spin accordingly, we glimpse their Republican rivals doing the very same. The debate itself, at least on a substantive level, is just window-dressing. What really matters to the filmmakers’ camera is the transparently smarmy business of political spin —something rendered with the cinéma vérité swagger you’d expect from a documentary about rockstars.

This scene is a paradigmatic example of how thoroughly the machinery of modern politics has eroded whatever membrane once existed to separate spectacle from reality. There is no longer, so it seems, any fourth wall to be had, and a film like The War Room quite openly invites us to celebrate this fact.

All hail the meta-narrative

Politics has always involved competing narratives — a truism no less applicable before the advent of television, radio, and mass communications. Today, however, we are confronted with something radically different when it comes to political narratives of every kind: a world in which their status as narratives has been absorbed into the consensus reality of politics itself.

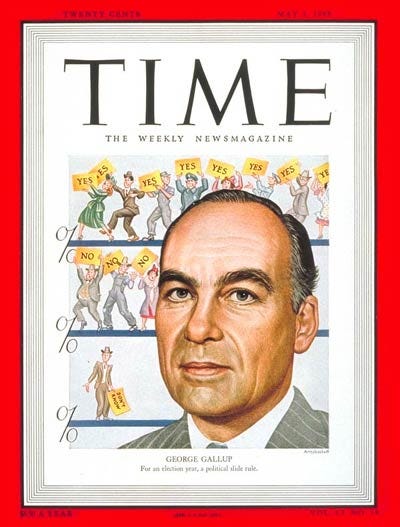

Collectively, we now overwhelmingly discuss all things political in the abstract register of “optics” and perceptions. Alongside credentialed members of the media, the politically-engaged citizen is encouraged think like a pundit who assigns Nate Silveresque abstractions like “electability” to politicians and pours over poll numbers to determine their own preferences.

This, I think, has largely come from the top. For decades, political TV has been dominated by panel shows in which pundits offer something roughly analogous to sports commentary.1 Quite often, the guests themselves are paid spin doctors, consultants, communications professionals, or some nebulous combination of all three.2 As people whose job is essentially the political version of marketing (and who sometimes quite literally work for private sector clients as well) their task is to watch the likes of speeches, press conferences, or debates and tell us who “sounded” the best. Notwithstanding whatever partisan allegiance they might officially have, if they evince clear beliefs outside the realm of style and optics, it can sometimes feel almost incidental.

I have never forgotten a broadcast I saw on the first day of one Canadian federal election, in which a major network devoted an entire segment to interviews with former campaign staffers who were asked to talk about the major parties’ campaign launches and rate their effectiveness. The discussion wasn’t about the content of what had been said at all, but rather the logistical machinations of campaign launches and how well these ones had worked as political setpieces. “What goes into planning an event like this?”, I remember the host inquiring at one point, later asking the panelists to rate each launch the same way you’d ask a panel of marketing professionals to rate different brands’ advertising campaigns for competing versions of the same product. Did Party X convey a message on the economy that will resonate with the middle class? Will Party Y’s launch effectively allay concerns it can be trusted with the public purse? Just how good are these political leaders as salespeople?

The cadence of programming like this is basically post-ideological — it being self-evident that leaders and political candidates are all actors and that all of this is principally theatre. The main question before us is who puts on the most convincing performance.

Partly for professional reasons, the superficiality of this style of political analysis has been a longstanding irritation of mine. In media interviews of various kinds, I sometimes find myself being asked to appraise politicians, pieces of rhetoric, or campaign strategies in a view-from-nowhere fashion that’s purely cosmetic. As someone who is fascinated by politics and writes about them for a living, I can’t pretend to be totally above pondering these kinds of things. As an ideologically committed person, however, I’ve long despised the fact that this has become the default register of political conversation in the media and beyond.

The machinery of bullshit

I am similarly irked by the ubiquity of opinion polls, both in election coverage and everyday political discourse. Back when I was a political staffer myself, I saw up close how much the work of campaigns now has to do with creating the impression of momentum as opposed to building the genuine thing. A favourable poll is now, in one sense at least, less valuable because of the support it might be registering than because it’s an effective weapon in the broader metanarrative battle that has so heavily come to shape campaigns. Polls used to be something confined to media reporting. Today, they are regularly cited or invoked by parties with a view to shaping voter behaviour, and in turn by voters themselves.

In obvious ways, this has the effect of pulling campaigns and politics as a whole away from real questions of policy and ideology. When the role of operatives is more to shape and contest the public metanarrative than to persuade people about the merits of a platform or policy, politics becomes much less substantive by definition.

Ultimately, however, the issue I’m concerned with here extends well beyond the likes of shallow panel shows, polling mania, or a culture that celebrates the smarmy maneuverings of backroom operatives.

One of the central ironies and paradoxes of modern politics is that the vast machinery of quantification that has come to pervade more or less everything — the analyses of pundits, the calculations of politicians and political parties themselves, the preferences of voters — has increasingly achieved the opposite of what it was supposed to do. From opinion polls and focus groups to elaborate studies of voter behaviour and voter psychology, to social media analytics and metrics, every facet of modern politics has gradually been suffused with technologies of objective measurement that ostensibly enable us to understand what we collectively want, think, and feel.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Luke Savage to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.