The paucity of Abundance

The hotly-debated new book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson is a grand sketch of liberalism's future that fails to reach beyond the lean horizons of its present

This is my longest Substack piece to date. Because it’s so lengthy and because I’d like it to be read as widely as possible, I’ve decided to forego the usual paywalled piece for this week. In light of that, you’d be doing me a solid by sharing and subscribing. Enjoy.

If you regularly spend time on the political corners of social media, you’re probably at least vaguely familiar with the discourse surrounding Abundance, the new book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. If you’ve gathered even a faint sense of what this book is, you may also be wondering what exactly people seem to be getting so worked up about.

The three basic thrusts of Abundance are 1) that various administrative and regulatory costs associated with building in essential areas like housing have grown too high and too cumbersome; 2) that invention and innovation are being stifled for similar reasons and because of risk aversion; 3) that the reigning ethos in American politics and policymaking — especially among liberals and “the left”, to whom Abundance is primarily addressed — has become one of scarcity. The authors’ proposed solution is basically to remove said barriers and enable the building of abundant goods and infrastructure in critical spheres like energy and transportation, as well as housing.

Most of this scans as quite familiar, even banal. Indeed, before reading the book myself I couldn’t really understand what exactly about these ideas was supposed to be new or why so many people — left, right, or centre — have been so consumed with either defending or debunking them.

The explanation, I think, is that Abundance actually does several very different things at once — some of them sweepingly grand, some laboriously granular. Having set out the fairly straightforward premise that certain costs are inhibiting supply, Abundance offers us a series of discrete ideas related to the likes of zoning policy and high speed rail. But, from its first pages, the book also presents itself as an epochal political manifesto sketching the outlines for an entirely new kind of liberalism.

In this spirit, it begins by presenting us a utopian sketch of a future in which scarcity has disappeared and elemental problems like hunger and environmental degradation have been solved. A few dozen pages later, we’re reading about the intricate history of zoning rules in American cities. Similarly, in its conclusion, a matter-of-fact survey of the Biden administration’s failure to get electric charging stations built pivots dizzyingly to a flourish about Marx’s theory of production in the span of just a few sentences.

Throughout the book’s roughly 220 pages, its register swings wildly from one of grandness to one of hyper-specificity and back again; its perspective oscillating between the arcane concerns of wonks and resplendent grand narratives of past, present, and future. In some places, Abundance reads like a quasi-spiritual case for a new age of social and material fecundity; in others, it seems to be motivated by the much more contingent frustrations of liberal policy experts with Democratic governance in coastal metropoles.

So, is this an ambitious political treatise, or a much more narrowly-focused grab bag of ideas, insights, and questions?

The answer is that it is very much trying to be both, and I think this is the main reason it’s ignited such contentious discourse. If Klein and Thompson had framed their book as a technocratically-minded intervention into a series of specific policy areas, it’s doubtful it would be selling so well or provoking as much discussion.1 From its earliest pages, however, Abundance is quite explicitly billed as an epic manifesto advancing a radically new way of thinking about politics, economics, and society. More than anything else, this panacea approach is central to both the authors’ stated project and the book’s purported novelty. It’s also central to many of the criticisms levelled by reviewers so far, and for good reason. If something is presented this way, it’s more than fair to critique its arguments with as broad a scope as the one Klein and Thompson have afforded themselves.

With all of that in mind, here are some more specific thoughts on Abundance.

1) Some of the ideas are perfectly fine

When it comes to the specific policy arguments and case studies found in Abundance, it’s worth saying that some are perfectly decent and non-controversial — even to a leftist like myself deeply skeptical of both mainstream liberalism and liberal wonkery. As Malcolm Harris noted in his review for The Baffler, the likes of permitting single-stair apartment buildings, ending single-family zoning, and eliminating parking requirements are worthy ideas when it comes to housing reform.

There’s also no reason the book’s frequent targeting of Democratic policymaking in big cities should necessarily scan as conservative or right wing. Going after blue city (or state) governance is fine in my books! At the federal level, Democrats tend to blame institutional blockages and Republican obstruction for their own failure to advance progressive policies or legislate major reforms. But there are plenty of states and cities where the party enjoys trifecta control of government and still governs from the centre right. If the defence national Democrats like to make about their lack of results were true, Rhode Island and New York would be like Sweden under Olof Palme.

I’m certainly no expert on the intricacies of the state’s policymaking, but the following portrait of blue California offered in the book’s introduction is impossible to disagree with and no one can blame Republicans: “California has spent decades trying and failing to build high-speed rail. It has the worst homelessness problem in the country. It has the worst housing affordability problem in the country. It trails only Hawaii and Massachusetts in its cost of living.”

Another worthy observation in Abundance is that the consumer economy has ballooned to the detriment of other essential goods:

An uncanny economy has emerged in which a secure, middle class lifestyle receded for many, but the material trappings of middle-class success became affordable to most. In the 1960s, it was possible to attend a four-year college debt-free but impossible to purchase a flat-screen television. By the 2020s, the reality was close to the reverse. We have a startling abundance of the goods that fill a house and a shortage of what’s needed to build a good life. We call for a correction. We are interested in production more than consumption.

I find little to disagree with here. In modern postindustrial societies, there has long been an excessive reliance on the relentless stimulation of demand through the production and marketing of consumer goods. In the United States, where consumption has more or less been elevated to the status of a civic religion, the problem is especially acute. The upshot is that an absolutely gargantuan quantity of capital, goods, and expertise that could be invested in more useful things is instead allocated towards an endless churn of cheap products and junk.

2) The book’s scope is far too wide…

Even in its more granular sections, the sweeping nature of the analysis in Abundance — and the corollary need to relate everything back to the same central theme — has an unhelpfully flattening effect. Here, I’m unable to improve on what Mike Konzcal says in his review::

Folding so many developments and trends under one rubric, from federal research to administrative rule-making to local zoning regulations, can obscure many of the individual challenges. These are genuinely distinct problems, each demanding its own solution and each facing its own coalition of resistance.

It would be unfair to expect a completely magisterial analysis from a book like Abundance. But there are clear problems inherent in its overriding impulse to structure everything around the same basic conceit.

3) …and also much too narrow.

For all its trading in bigness and grand narrative, there are so many obvious things missing from the book’s account, and in particular its account of where the present torpor supposedly afflicting both political institutions and the wider liberal imagination really comes from.

Where are monopolism and the financialization of America’s economy in this story? Where is the concerted political effort to destroy the labour movement? And where is the corporate capture of the Democratic Party — in part a direct result of the political project initiated by Bill Clinton — in this book’s account of where liberalism has gone astray? The Democratic Party hasn’t become impotent, ineffective, and unpopular simply because it’s ideas are stale. And, if they are, it’s principally because both the Democratic apparatus and the intellectual braintrust that generates those ideas are so dominated by powerful corporate actors with parochial interests and deep pockets.

Rather than confront any of this, the story offered to us in Abundance appears to blame environmentalists and public interest advocates like Ralph Nader for demanding too many regulations since the 1970s. Elsewhere, it indicts the individualist (and, by implication, selfish) ethos championed by the New Left, which today ostensibly lives on in unequal, over-regulated blue metropoles and the NIMBYist homeowners who have captured their policymaking regimes:

In the 1970s, the New Deal order collapsed beneath the weight of crises it could not contain—stagflation and the Vietnam War, most notably. But there was more to it than that. Abroad, the horrors and absurdities of communism became clearer. At home, millions of oppressed Americans marched, sat-in, and organized for rights. A change in values took hold. The promise of collective action lost its luster. Nurturing the dignity and genius of the individual, in the face of regimes that seemed to squelch both, became the reigning ethos.

This, to me, is an absolutely baffling way to account for the decline of social democratic collectivism in American life. Just as American socialism was thwarted through the direct efforts of the state and private industry, the liberalism of the New Deal and Great Society eras — both in a literal institutional sense and an ideological one — was gradually undone by a competing political (and class) project that mobilized vast support from corporate America and wielded it to capture the state.

We don’t need pop sociology or quasi spiritual narratives to explain the decline of communitarian liberalism. The explanations are material and political.

Finally, as a few have pointed out, Abundance is notable for its lack of a global perspective. If there’s going to be a brave new world of abundance for all, it will presumably be resourced at least partly with materials and goods from outside the United States. Who is going to extract them? How much will they be paid? What kind of global trade regime does the Abundance Agenda require?

Given the book’s panacea approach, these are all perfectly fair questions to ask.

4) The book’s holes and blind spots only invite larger questions

It’s no exaggeration to say that Abundance’s dizzying fusion of grandness and granularity often make its analysis and its prescriptions difficult to firmly pin down. At times, Klein and Thompson really do seem to be telling us that a suite of regulatory changes in major cities represent a comprehensive agenda for liberals that will, in turn, engender a radical paradigm shift toward the utopia described in the book’s introduction. But their proposals are also often so banal-seeming it’s unclear how this can possibly be the case, or what exactly is supposed to be groundbreaking here.

As Zephyr Teachout puts it in her perceptive review:

[the proposed zoning reform] would still seem relatively small-bore as a novel solution: Half of the 10 biggest cities in America—many in Texas—already have a zoning and procedural regime fairly close to what Klein and Thompson want. Are they simply arguing that Dems embracing Texas zoning approaches would transform national politics? That can’t be it…I can’t tell after reading Abundance if the authors are seeking something fairly small-bore and correct (we need zoning reform) or nontrivial and deeply regressive (we need deregulation), or if there is room in the book for anti-monopoly politics and a more full-throated unleashing of U.S. potential.

Throughout this book, we frequently find the political minimalism reflexively favoured by centrists disguised in a language of futurist grandiosity. In far too many places, the authors opt to hedge their bets ideologically (e.g. “It is childish to declare government the problem. It is just as childish to declare government the solution. Government can be either the problem or the solution, and it is often both.”) while leaving big questions unanswered.

I’m still not sure I know what role they envision for the state in the utopian future sketched by the book’s introduction. It certainly sounds like something that would require coordinated planning to bring about, but the book is scant when it comes to substantive discussion of economic planning and evasive in its attitude towards the state.

5) One of the load-bearing narratives of Abundance is just plain wrong

Few things in this book baffled me more than the backstory its authors provide about the state of American liberalism. They write:

“For decades, American liberalism has measured its successes in how near it could come to the social welfare system of Denmark. Liberals fought for expansions of health insurance and paid vacation leave and paid sick days and a heftier earned-income tax credit and an expanded child tax credit and decent retirement benefits. Worthy causes, all. But those victories could be won, when they were won, largely inside the tax code and the regulatory state. Building a social insurance program does occasionally require new buildings. But it rarely requires that many of them. This was, and is, a liberalism that changed the world through the writing of new rules and the moving about of money.”

Where does one even begin? At no point in my lifetime has the Democratic Party or its intelligentsia embraced or meaningfully pursued a project that even remotely resembles Nordic social democracy. If anything — as the 2016 and 2020 Democratic primaries particularly attest — modern liberalism has partly defined itself in opposition to exactly such a project.

And it’s in a related passage early in the book’s introduction that we begin to see a neoliberal subtext operating beneath the intoxicating vistas dangled by the authors:

Progressivism’s promises and policies, for decades, were built around giving people money, or money-like vouchers, to go out and buy something that the market was producing but that the poor could not afford. The Affordable Care Act subsidizes insurance that people can use to pay for health care. Food stamps give people money for food. Housing vouchers give them money for rent. Pell Grants give them money for college. Tax credits for child care give people money to buy child care. Social Security gives them money for retirement. The minimum wage and the earned-income tax credit give them more money for anything they want.

To be clear, Klein and Thompson are quick to add that they support this stuff. But little if anything in what they describe here resembles Nordic welfarism. As Matt Bruenig points out:

The Nordic countries don’t use means-tested tax credits to provide cash benefits to children. They just send all of the kids a check each month. The Nordic countries don’t expand health insurance via means-tested tax credits and mandates to buy private health insurance. They have universal public insurance. (On this point, the authors miss a chance to see how the inefficiency and administrative burdens they loathe in construction actually plague the welfare state too, something liberals are very much to blame for but also have no desire to fix.)

Once again, the book’s attitude towards the welfare state is incredibly unclear. It’s erroneously asserted that America’s liberals have too zealously pursued a north European model of political economy (????) but the social policies actually outlined mostly take the form of means-tested cash payments or — as in the case of the Affordable Care Act — public subsidies for the private sector.

6) So just what the hell is really going on here?

Abundance is billed as a friendly critique of progressivism (or, as the authors put it, of “the pathologies of the broad left”) from within the bosom of American progressivism itself. Klein and Thompson are both liberals who care about things like climate change and the lack of affordable housing. But, in seeming to conflate the Obama era liberalism of means-testing and tax credits with Scandinavian social democracy, I think they are really feigning self-criticism in service of the all-too familiar goal of punching left.

Some of the clearest evidence comes in the book’s conclusion, which explicitly situates the Abundance Agenda as a centrist alternative — a “third way”, if you will — to both the populist left and the authoritarian right:

Today’s politics are suffused with cynicism and pessimism about government because “a way of living sold to us as good and achievable is no longer good, or no longer achievable.” In 2016, the rise of Bernie Sanders on the left and the rise of Donald Trump on the right revealed how many Americans had stopped believing that the life they had been promised was achievable. What both the socialist left and the populist authoritarian right understood was that the story that had been told by the establishments of both parties, the story that had kept their movements consigned to the margins, had come to its end.

I have many complaints about the framing in this passage (and if you’ve ever read my work they’ll be so familiar I don’t need to detail them here). But I strongly disagree with how the authors so lazily associate a project like Sanders’ with the scarcity mindset they deride. If Sanders-ism is about anything, it’s quite literally abundance — abundance of free healthcare, of free higher education, of union jobs, of high wages, of public goods in general.

These things, however, are fundamentally about redistribution, and it’s here that the book’s point of view slides furthest into a rhetorical mode that would be comfortably at home on a panel at the World Economic Forum or the Aspen Ideas Festival. For example:

When you grow an economy, you hasten a future that is different. The more growth there is, the more radically the future diverges from the past.

The authors, for what it’s worth, do not explicitly reject redistribution. But in an incredibly unsatisfying hedge, they deem it “important…but [also] not enough.” It’s here that my own philosophical differences with people like Thompson and Klein are probably the most profound. What the two of them so effusively believe about growth is more or less what I think about redistribution. Which is to say: when you redistribute wealth, you in fact hasten a present that is radically different from the one we currently know.

In an unequal society where the majority must invest the lion’s share of their time and energy into the labour required to obtain the bare necessities of life, individuals lose much in the way of personal freedom and life satisfaction. But we also collectively sacrifice unfathomable quantities of human creativity and potential. There might be abundant growth, but that can matter very little if its fruits aren’t broadly shared.

Redistribution does not equal, as Klein and Thompson assert, a mere “parceling out of the present.” In a very different sense than theirs, it represents its own agenda of abundance — one reflecting the richest egalitarian ideas of the 19th and 20th centuries. The liberalism of the 21st might reject those ideas, but many of us on the left still see them as indispensable. Socialism, contrary to what many of its critics have historically claimed, is first and foremost concerned with human freedom: freedom to think, freedom to dream, freedom to create, freedom to live unburdened by toil, freedom to imbibe the bountiful experiences of life, freedom to do absolutely nothing at all. Equality is merely a means to that end.

Klein and Thompson appear to believe distributional questions can be mostly elided if enough new technology is invented and a sufficient quantity of stuff is built and produced. Contentious debates about degrowth aside, I find this assertion vastly more improbable and utopian than the project of universal social welfare or the realization of social and economic rights. Scientific and technological innovations can be hugely beneficial, but until we live in the world of Star Trek: The Next Generation it’s unlikely they will ever compensate for the dearth of social and economic justice. Issues like poverty or hunger are not technical puzzles we can simply invent our way out of, and the sorts of measures and programs needed to remedy them don’t require any great leap in our technological capacity.

Moreover, the book’s lack of specificity and detail when it comes to the role (or non-role) for redistributive and welfare state policies in the Abundance Agenda can only leave us to conclude the authors do not see moving beyond the vision of tax credits and cash payments that has largely defined post-Clintonite liberalism as a priority. Abundance includes five chapters entitled “Grow”, “Build”, “Govern”, “Invent”, and “Deploy”. There is no chapter called “Provide” because the authors see the meeting of social needs as downstream from the abundant growth they hope to foster.

7) Haven’t we been in Kansas all along?

I have said less about the parts of Abundance dealing specifically with innovation. For what it’s worth, there are some apt observations about the importance of public sector investment to the birthing of new technologies. But this is confusingly in the service of an approach to innovation that sounds remarkably similar to the one America’s leaders and politicians — especially in California — have already opted to take. While there there is a more critical mention of Elon Musk in the book’s conclusion, here’s how he’s described midway through:

“Musk has become a lightning rod in debates over whether technological progress comes from public policy or private ingenuity. But he is a walking advertisement for what public will and private genius can unlock when they work together.”

The truth here is quite the opposite. Among other things, Elon Musk is clear testament to the dangers of throwing billions of dollars of public money in the direction of unaccountable tech barons. But even if you don’t agree, the American state’s addiction to Musk has helped make him the richest man in the world. In light of that, hasn’t the necessary fusion of “public will and private genius” already been achieved?

8) Even if you’re fully abundance-pilled, how do you sell and realize it as a political agenda?

In her review, Zephyr Teachout raises an important and hitherto under-discussed question:

A minor question I had throughout is whether their theory means that abundance cannot be a popular public movement until it succeeds, or whether they also believe that abundance could be an organizing principle for a grassroots bottom-up movement before any reforms have been implemented.

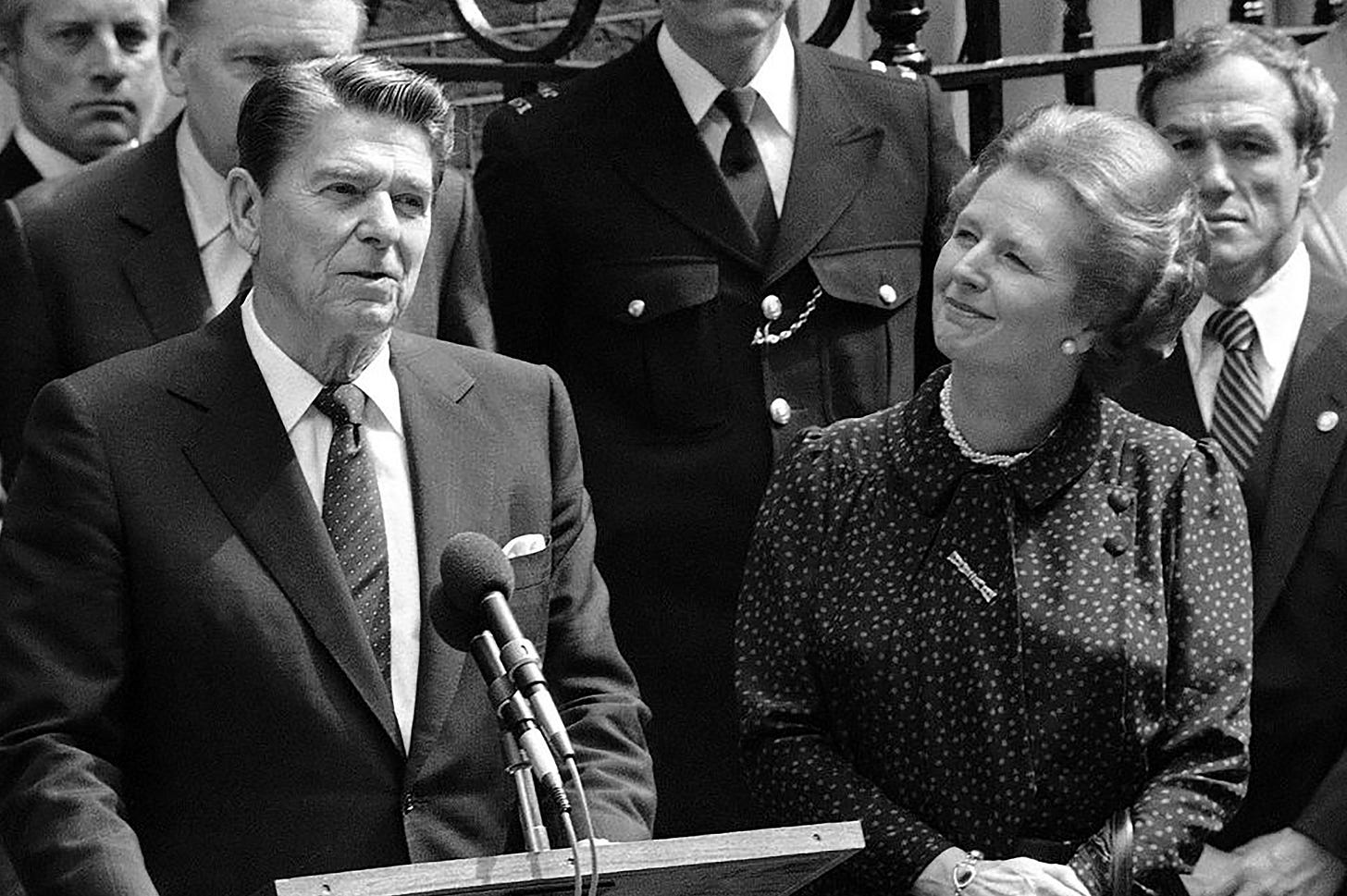

I suspect she’s just being diplomatic here, because this question doesn’t seem minor to me. If Abundance is meant to be the foundation of a new liberal agenda, how do its advocates plan on translating it into a popular offering that will be attractive to voters? In the introduction, Klein and Thompson say a “counterforce” to scarcity thinking is emergent but young. In the conclusion, they cite academic Gary Gerstle to the effect that establishing a new political order requires “advances across a broad front.” It needs “deep-pocketed donors”, think tanks, policy networks, candidates, and an inspiring moral message. They then invoke both FDR’s New Deal and Reaganism as instances of a new political order coming into being.

In one sense, there is an equivalency to be drawn here. But FDR’s effort was, first and foremost, a mass and popular one rather than something partly astroturfed by lushly-financed think tanks and corporate elites. With those in his pocket, Reagan confronted elements of the postwar state and smashed the American labour movement. Clearly, these things are not the same.

Notwithstanding the grand utopian narrative they’ve attached to it, the project Klein and Thompson describe certainly seems like one whose vanguard will come from established elite networks in top-down fashion. A few weeks ago, I wrote about the former’s recent conversation with one Massachusetts Congressman who is a proponent of the Abundance Agenda, and I find it very difficult to imagine his rather convoluted style having wide popular appeal.

9) The seductions of syncretism

We often think about big political and economic questions in terms of dichotomies: Capitalism vs. Socialism; central planning vs. laissez-faire; big government vs. small government; equality of opportunity vs. equality of outcome; supply vs. demand. Sometimes these reflect objectively hard barriers between different ideologies and concepts, and sometimes the boundaries are much more contestable and porous.

If you’re looking to make a story about politics or a particular political vision sound novel, one of the easiest ways is to fold traditionally opposed ideas into one another. Occasionally in history, an authentic version of this process has occurred. Since the late 20th century, however, we have been living through a period of world historic paralysis and stagnation when it comes to new ideologies and new ways of thinking. Yet we are also relentlessly bombarded by supposedly grand new projects and theories whose claims to newness are ersatz at best.

“Nudging,” (or “libertarian paternalism” as it was also called) was an ostensibly revolutionary synthesis of Reaganism and the New Deal briefly in vogue during the breathless early days of the Obama presidency. Stripped of artifice, nudging was actually just a dull riff derivative of the so-called Third Way — a project that, at least in its most utopian form, was supposedly going to resolve the tensions of market, state, socialism, and capitalism for good.

The Third Way was intellectually and psychologically compelling because it purported to synthesize the best of 20th century ideology while eschewing all that was bad, sclerotic, or stale. The Third Way, however, was functionally just the new and intensified form of capitalism we have come to call neoliberalism.

As its promises and assumptions have been discredited, neoliberalism has suffered a spiralling crisis of both intellectual and popular legitimacy. To put it bluntly, Abundance must ultimately be seen as just the latest effort to make what’s old appear new and get the proverbial engine running again.

When its authors warn that American politics are “stuck between a progressive movement that is too afraid of growth and a conservative movement that is allergic to government intervention” they are engaging in a kind of intuitively attractive rhetoric that seems to make the usual tradeoffs vanish before our very eyes.

More importantly, they are presenting us with a grand vision of a new liberalism that in both analysis and prescription strongly resembles the one we already know: a liberalism that elides fundamental questions of class and power and views both the authoritarian right and the populist left as equivalent adversaries; a liberalism that reduces political problems to vaguely-defined social pathologies while rejecting mass democracy; a liberalism that eschews all but the most barren welfarism and invests an almost religious faith in the capacity of private actors — be they developers or tech barons — to build and innovate in the public interest if given the right incentives and liberated from constraint.

The authors’ particular emphasis on supply allows them to make solid observations about the shortcomings of the consumerist economy. A liberalism that actively tries to get necessary things built, moreover, is clearly preferable to one that doesn’t. But New York and California are not the world, and overcoming the style of governance favoured by neoliberal Democratic machines in those states will also require a project more confrontational and heterodox than one whose front-facing pitch amounts to slackened zoning regulations.

In the idea of supply-side liberalism, I find it hard not to see the ghosts of syncretic micro-philosophies past. But in a moment where the far right has seized control of the world’s most powerful state and the populist left has been at the forefront of mobilizing the opposition, I also see a liberal class still clinging desperately to the ossified shibboleths of centrism and throwing everything it can at the wall in the hope that something, anything will finally stick.

The authors appear to have considered this approach and rejected it. In their conclusion, they write: “We considered calling this book “The Abundance Agenda.” We could have easily filled these pages with a long list of policy ideas to ease the blockages we fear…It is easy to unfurl a policy wish list. But what is ultimately at stake here are our values. How do we weigh the role that the current inhabitants of a community should have in who enters that community next? How do we balance the interests of a town against the interests of a country?”

Your description of what freedom means -- or ought to mean -- was bracing and is rarely heard in these parts.

Americans struggle to give it that abundantly (yes, indeed!) generous definition. The stirring tones of the Proclamation of Emancipation could have been a start and FDR's Four Freedoms did hint at a guarantee of something more than mere subsistence but the effort stalls soon after that. We look back at what Gary Gerstle calls the New Deal Order with fondness, a type of Fordism on a national scale for the country's white population. Even so, we tell ourselves, it was far better than the Social Darwinist alternatives from the Gilded Age that reactionaries like Robert Taft and Fred Hartley wanted us to return to. Yet it was just a matter of time before the dismantlers would succeed and they made their first move with the 1973 Powell Memo, still worth reading as the guiding spirit for today's Project 2025.

As you point out in your review essay, but in a too circumlocutionary way, this book is In the spirit of Gerstle. Klein and Thompson -- with their fellow travelers, Noah Smith and Matt Ygelsisas -- want to claim the mantle of that New Deal Order but substantially reworked and without a jot of the redistributionist and regulatory force of the original program. In fact, they would happily identify with deregulatory zeal of the current Gilded Age for large swathes of the economy.

Their vision then amounts to this: "efficient" delivery of "public goods" that increases the "productivity" of the economy. (Quotation marks only to emphasize their touchstones.) From this, we get the non-zero sum game. Workers receive cheaper and better housing, child care, health care, education, social insurance, etc., thanks to government investment while the private-sector gets highly productive and economically secure labor input and can count on high growth to sustain their drive for profits.

This not how capitalism works, or has ever worked. The primeval drive for profits is maximal and all-consuming. Michael Kalecki told us, capitalism needs -- even requires -- the insecurity of workers to survive. Private capital in a market economy is savage, predatory and will use politics, the law, technological innovation, whatever, to suck the marrow of economic value to usurp for itself. It must necessarily be shackled.

Your conclusion was right on the mark. The book is another artful attempt to salvage the discredited belief system known as neoliberalism. Lipstick on a pick? Quite possibly.

“The paucity of abundance” well done, Luke. You’re embracing Marx on title shithousery.