The populism of fools

On the phony class politics of conservatism

The casting of Donald Trump as a populist figure has been part and parcel of the Trump brand for years, and has found plenty of buy-in among admirers and detractors alike. Still, it’s rare to see the idea expressed quite as explicitly or absurdly as it was in a recent tweet by Bari Weiss (who was, for context, quoting from an article by Eli Lake published on the day of Trump’s inauguration):

The rejoinders to this sentiment are so obvious it’s almost embarrassing to write them. If Donald Trump, a billionaire and now two-term president, is an “enemy of the ruling class,” after all, then words might as well mean anything. In addition to Trump’s personal wealth, his presidency is proudly backed by some of the world’s richest people, the net worth of the tech barons who were given pride of place at his inauguration being more than a trillion dollars. The biggest legislative accomplishment of Trump’s first term in office was a massive tax cut whose main beneficiaries were overwhelmingly the upper echelons of the top 1%.

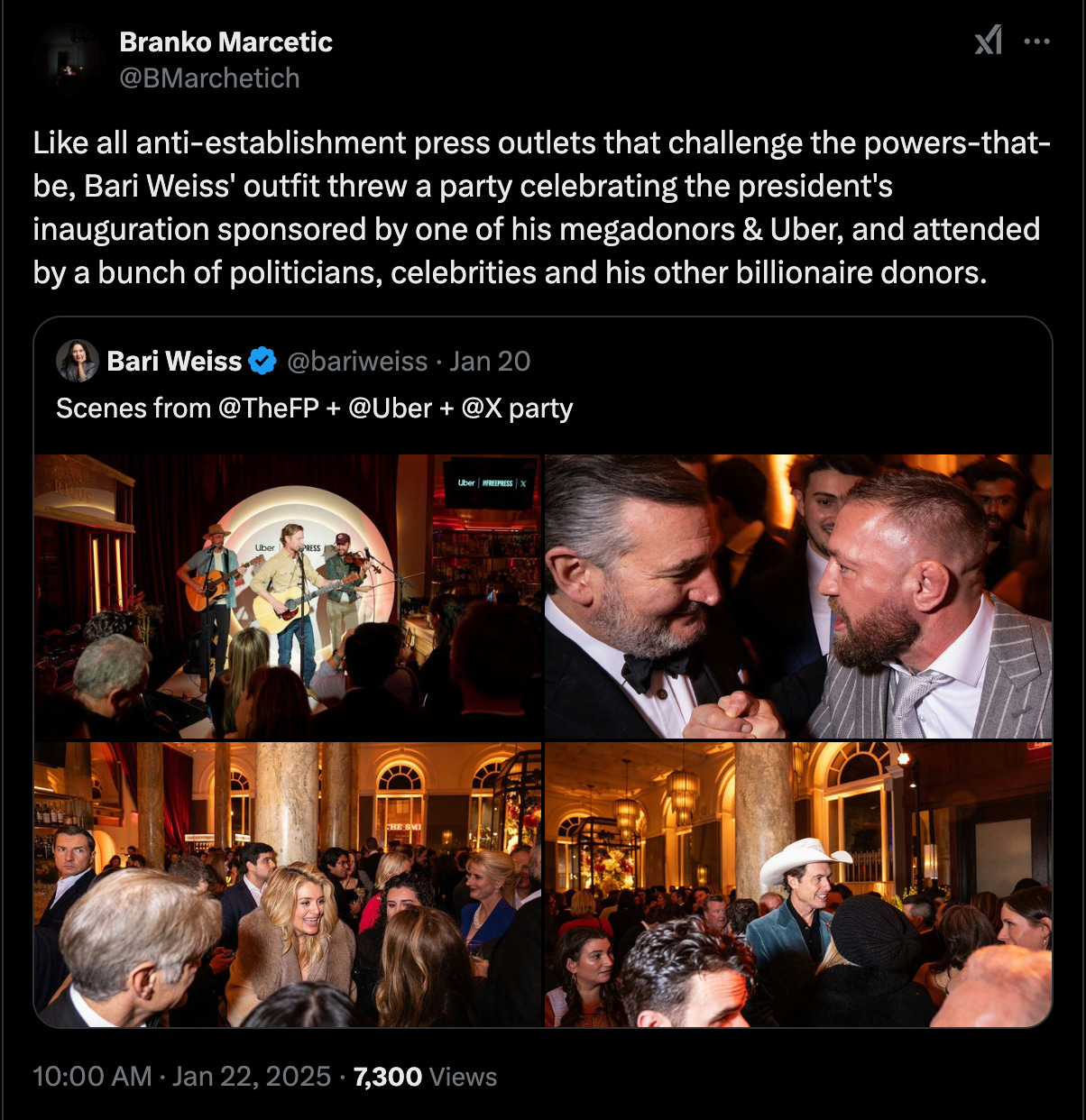

For Weiss’s part, her own inauguration day responsibilities included hosting a chic soiree sponsored jointly by salt of the earth mom and pops X and Uber. (For good measure, the do itself was effusively written up in a tabloidesque piece for Weiss’s publication The Free Press that was devoted, near exclusively, to cataloguing all of the rich and famous people in attendance.)

Because it’s so obviously stupid on its face, the notion of Donald-Trump-as-scrappy-populist is easy enough for those of us who aren’t on the right to mock and dismiss. But if we engage the idea on its own terms I think we can also observe something important about the particular way conservatism tries to delineate class-inflected categories like “the people” or “elites.”

Here, the definition of populism offered by Lake in his article is both useful and clarifying:

Populism is hard to pin down. It’s not really a governing philosophy or a movement or an ideology. Some call it a political grammar that pits the people against the powerful, the best of us against the rest of us. It’s more of a mood, the desire to fire the bosses, crash the country club, and ask the snobs: You think you’re better than me? And every now and again, populism in America can sweep an old order out of Washington. Populism is Sam Adams and his friends dressing up as Mohawks and dumping imported tea into Boston Harbor. It’s the protagonist in a John Grisham novel discovering that the whole damn system is corrupt. It’s Walt Whitman’s “barbaric yawp.” It’s Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights quitting on the set of a porno, screaming, “You’re not my boss! You’re not the king of me!”

I’ve often found the ubiquity of “populism” in post-2016 discourse to be unhelpful — in part because it’s tended to refer more to a particular kind of political style than to anything more concrete (I went into this in an essay for The Walrus back a few years ago). It’s precisely this quality, however, that attracts Lake to the term: populism might imply a rebellion of some kind pitting “the people against the powerful” but, beyond that, the exact contours of those categories (and others related to them) in effect become a choose your own adventure — a question of attitude, affect, and outlook rather than wealth, social location, or institutional power. In the reactionary imagination, terms like “populism”, “elites”, and “the ruling class” connote vaguely-defined dispositions more than they do coherent analytical categories; their boundaries endlessly malleable; their foundations more cultural than material.

It’s a nifty sleight of hand, in that it allows conservatives to attach the form and rhetoric of class politics to more or less whatever they like while effectively taking the politics out of them. And thus, in one fell swoop, tech oligarchs sitting at the very nexus of corporate power can become the faces of a “populist moment”; a billionaire president ringing in his second term a tribune of the hardworking masses.

The flipside, of course, is the avowedly anti-populist posture taken by so much of the liberal mainstream since 2016. If the right has been able to engage in the kind of phony populism I’ve been describing, one reason is that the centre — in its gleeful exaltations of elites, endless valourization of experts, obsession with celebrity, contempt for “deplorables”, and so on — has so willingly ceded the ground.

Heard about your Substack on Michael and us. Great news and keep up the positivity and analysis amidst the truly crushing shit show all around. He seems increasingly unhinged so maybe he will not last 4 years.

I think Peter Turchin’s explanation makes the most sense. What we are seeing is a different set of elites with wide public support. They want to change the bums in the seats of power and destroy the previous bums that were there.

There’s no desire for popular rule. If there was we would see devolution of power from the executive and adoption of bottom-up power structures in govt institutions.

Populist movements are empowering to average people, this movement is the opposite of that.