The Wasteland

Influencer culture shows us a bleak future where all life has become commerce and markets have conquered the private self

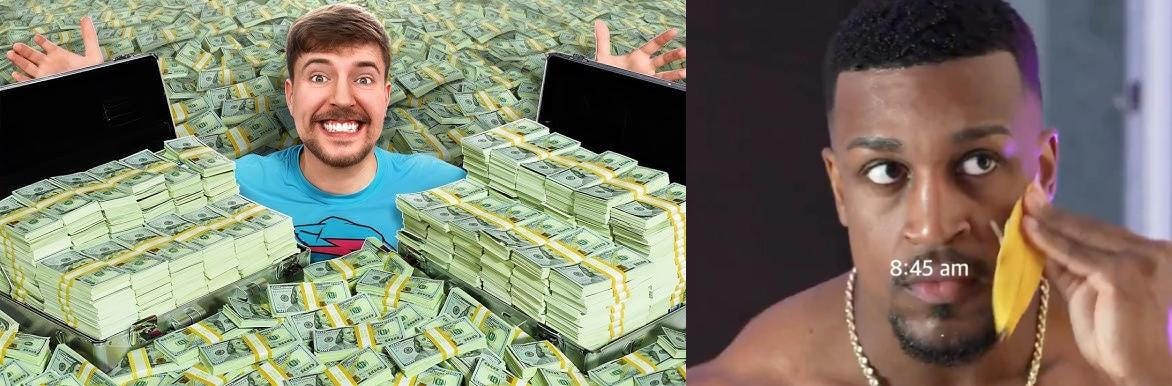

Until the other day, I had never heard of Ashton Hall. But he’s an influencer with millions of subscribers across various platforms, and the star of a recent viral video that boasts an astonishing 720 million impressions on Twitter.

Perusing Hall’s Instagram page (which has 10.7 million followers alone) it looks pretty par for the course for the genre. Hall maintains a lean and jacked physique. He wears chic blazers, drives sports cars, and wears expensive watches. He offers bland, generic lifestyle tips and preaches the kind of postmodern prosperity gospel that has conquered much of the online world since the 2010s. The videos themselves tend to be sterile and airbrushed, everything in them perfectly smooth and largely indistinguishable from more or less any male influencer doing the same schtick. Hall happens to be American, but apart from his accent he could just as easily hail from any number of places because the genre’s prevailing aesthetic makes the entire world look like a giant shopping mall in Dubai.

I got interested in Hall’s videos thanks to a recent exchange between Aaron Bastani and Ash Sarkar over at Novara Media. If you’re interested, you can watch their whole discussion, but for our purposes the relevant part is the two videos they include near the beginning:

These videos show us influencer culture at its most hollow and the grindset ethos at its most ridiculous. The image Hall projects is meant to be cool and aspirational. But he seems to spend the lion’s share of his day working out, eating by himself, and doing Patrick Bateman’s skincare routine.

As things are depicted anyway, he also seems to spend it mostly alone. Hall is alone at home. He’s alone in the gym. He’s alone at the swimming pool. And, insofar as other people do appear, it’s solely as props or appendages. As Bastani points out, the only times we actually see anyone else on camera (or even sense their presence outside the frame) is when they’re bringing Hall something or serving him food:

“[in both of these videos] he isn’t actually around anyone. He has no relationships to anyone. He’s just this little atomized unit: sharing content, making money, consuming. No partner in bed. No kids screaming. No parents to look after. No housemates. No nothing. Just this guy looking at screens all day, as well as his own reflection. The only time you see other people is when they’re doing something for him. And here’s where things get serious. Because if this is the vision of success we’re selling young people — as funny as it may be — where other people are clients or people serving you; [and] when you talk to anyone it’s via a screen; everything you do, from working out to eating, is done alone…Think about that for a moment and then ask: is it any wonder we’re seeing surging problems with mental health? If this is aspiration, what on earth is failure?”

Indeed, Hall might be an extreme case but something like this vision of aspiration now runs through much of popular lifestyle content.1 In an obvious sense, it reflects an ethos of success and personal fulfillment with clear roots in the worst excesses of gym culture (Patrick Wyman put this particularly well back in 2020). On a fundamental level, it’s also one deeply enmeshed in the calculi of markets — in many ways epiphenomenal of the metrics and algorithms that drive social media themselves.2 Hall himself, in fact, devotes plenty of videos to talking specifically about how he’s learned to juice the reach of his content and convert his viral numbers into monetary success.3

It’s quite bleak to think about. In obvious and disturbing ways, the incentive structures of digital media appear to be cultivating a vast cohort of young people — particularly though not exclusively young men — who are profoundly antisocial, and lack any real narrative of life beyond one of atomized hustle and endless accumulation. As Sarkar observes in the discussion above, the idea of “making gains” (borrowed from the world of bodybuilding) has, in effect, supplanted any notion of socially productive labour.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Luke Savage to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.